Archives | Papua New Guinea

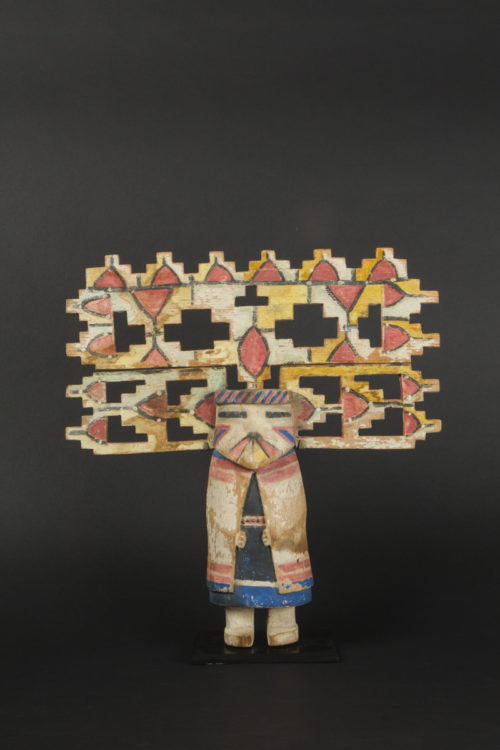

Yipwon

Papua New Guinea

War charm Yipwon

Middle Sepik, Korewori

Carved wood

Early 20th century

Height: 8 ½ in. (21.5 cm)

Ex collection Harry Franklin, Los Angeles

Ex collection Michael Hamson, Palos Verdes

Sold

Flowing through the neighboring chains of hills and swamplands, the Korewori River (formerly the Karawari) is one of the numerous tributaries of the Sepik, the river that sustains the populations of the eastern part of the island of Papua New Guinea.

The discovery of Korewori art (Middle Sepik) constituted a major intellectual and artistic shock for the West.

In 1960, the Museum of Primitive Art in New York showed Korewori hook figures for the first time, but it was not until 1968 that a groundbreaking exhibition dedicated to the art of this region, “Caves of Karawari“ was organized at D’Arcy Galleries in New York.

This exhibition allowed the public to discover an aesthetic combining boldness of form, modernity, and ferocity.

In the ancient art of the Yimam (Yimar) and Inyai-Ewa populations living along the Korewori River, the human body is transformed, stylized and reduced to two-dimensional volumes. The tall yipwon hooks and anthropomorphic spirit figures feature silhouettes punctuated with curves and sharply pointed elements interacting with empty and full volumes.

The resonance of the ancient art of the Korewori with the work of artists like Henry Moore, Roberto Matta and Alberto Giacometti is fascinating.

The ritual figures called yipwon were linked to hunting and warfare. According to one of the founding myths of the Korewori, the yipwon were children of the Sun, conceived from wood shavings that fell during the carving of the first drum. One day, prompted by his warrior instinct, one of the yipwon children committed a murder. Out of fear of reprisal, he took refuge in the Men’s House and turned into a wooden statue. Outraged by the behavior of his offspring, the Sun left the Earth, leaving the yipwon there, their mission henceforth being to serve as guides for men, in particular on head-hunting expeditions against neighboring enemies.

Large-scale yipwon belonged to the whole clan; they were kept in the Men’s House or in sacred caves reserved for religious ceremonies. Small-scale charms, like the one here, were personal and used by individual warriors.

Before going to battle, the yipwon were invoked to insure the success of the war party, becoming responsible for extinguishing the vital energy and fighting spirit of their enemies, thus making them vulnerable during battle. In case of victory, yipwon were celebrated during ceremonies, receiving offerings of libations. In case of defeat, however, they were abandoned.

Yipwon sculptures feature both the interior and the exterior of the body, skeleton as well as internal organs, and facial features. The rounded parts in the middle of the hooks symbolize the vital core that fires up the warrior spirit.

The discovery of Korewori art (Middle Sepik) constituted a major intellectual and artistic shock for the West.

In 1960, the Museum of Primitive Art in New York showed Korewori hook figures for the first time, but it was not until 1968 that a groundbreaking exhibition dedicated to the art of this region, “Caves of Karawari“ was organized at D’Arcy Galleries in New York.

This exhibition allowed the public to discover an aesthetic combining boldness of form, modernity, and ferocity.

In the ancient art of the Yimam (Yimar) and Inyai-Ewa populations living along the Korewori River, the human body is transformed, stylized and reduced to two-dimensional volumes. The tall yipwon hooks and anthropomorphic spirit figures feature silhouettes punctuated with curves and sharply pointed elements interacting with empty and full volumes.

The resonance of the ancient art of the Korewori with the work of artists like Henry Moore, Roberto Matta and Alberto Giacometti is fascinating.

The ritual figures called yipwon were linked to hunting and warfare. According to one of the founding myths of the Korewori, the yipwon were children of the Sun, conceived from wood shavings that fell during the carving of the first drum. One day, prompted by his warrior instinct, one of the yipwon children committed a murder. Out of fear of reprisal, he took refuge in the Men’s House and turned into a wooden statue. Outraged by the behavior of his offspring, the Sun left the Earth, leaving the yipwon there, their mission henceforth being to serve as guides for men, in particular on head-hunting expeditions against neighboring enemies.

Large-scale yipwon belonged to the whole clan; they were kept in the Men’s House or in sacred caves reserved for religious ceremonies. Small-scale charms, like the one here, were personal and used by individual warriors.

Before going to battle, the yipwon were invoked to insure the success of the war party, becoming responsible for extinguishing the vital energy and fighting spirit of their enemies, thus making them vulnerable during battle. In case of victory, yipwon were celebrated during ceremonies, receiving offerings of libations. In case of defeat, however, they were abandoned.

Yipwon sculptures feature both the interior and the exterior of the body, skeleton as well as internal organs, and facial features. The rounded parts in the middle of the hooks symbolize the vital core that fires up the warrior spirit.

Explore the entire collection