Archives | Arizona

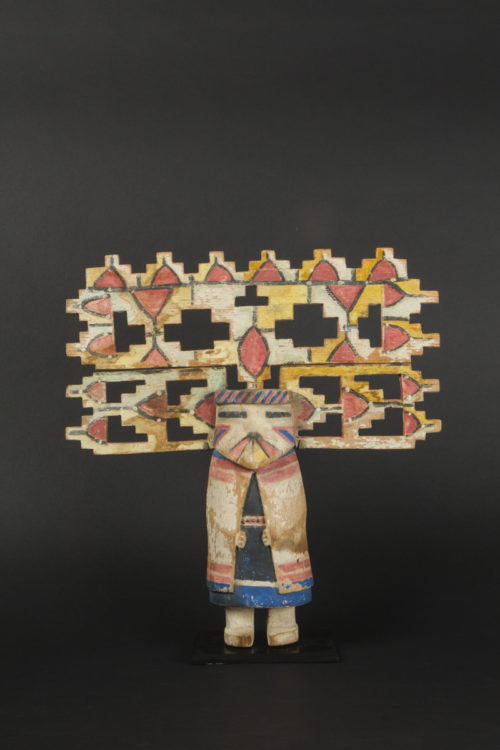

Kachina doll

Arizona

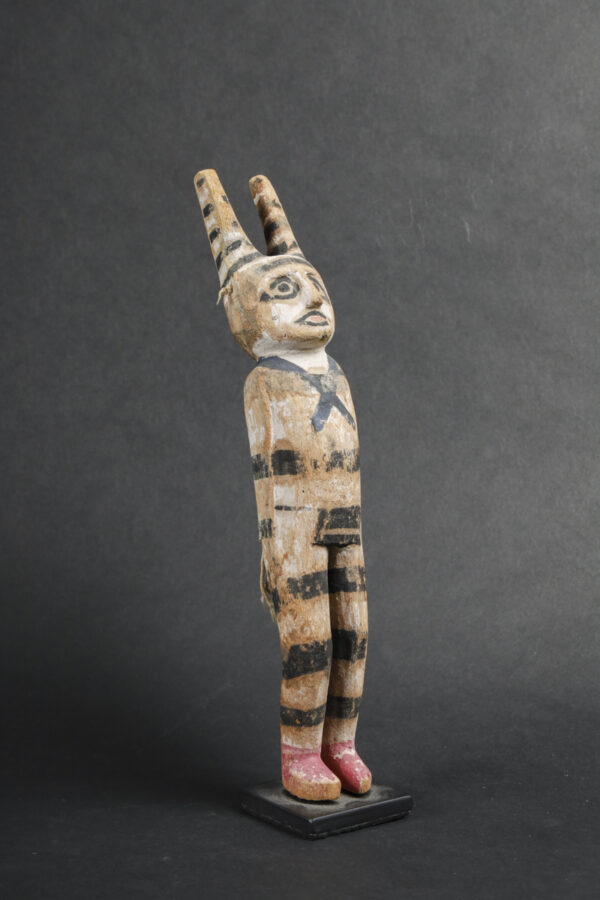

Koshare Katsina – Hano Clown Kachina doll

Hopi

Circa 1900s-1920s

Carved wood (cottonwood root) & pigments

Height: 25 cm – 9 ¾ in.

Provenance

Ex collection Steve Nelson, California since the 1970s

Sold

Kachina dolls (or katsinam) represent spirits or gods from the pantheon of the Pueblo peoples in the American Southwest. Given to children, kachina dolls constituted a teaching tool allowing them to familiarize themselves with the spiritual world and perpetuating knowledge of the founding myths on which their society was based.

The Kachina presented here is a representation of Koshare, the Hano Clown Kachina. It plays the role of a disruptor or troublemaker during ceremonial dances, teasing the Guard and Whipper Katsinam, mocking other dancers, and bringing humor to the spectators.

The Clowns played a significant role in Hopi ceremonies. Beyond the theatrical and comedic aspect of their appearance, they allowed the Guards and Warriors to maintain order and embody justice and wisdom. While the Guards often prevailed, there were instances where the Clowns got the upper hand, causing disorder and confusion at the very the heart of the ceremony.

This is not random but rather symbolically choreographed, illustrating inherent human tendencies. For the Hopi, the Kachina spirit community resembles that of humans: some members strive to conform to established order, while others constantly twist or break the rules. Far from being scorned, the Kachina Clowns are highly respected, feared, and admired. These "Masters of Disorder" represent what Roger Caillois called "the sacred of transgression" ("L’Homme et le Sacré", 1939).

During his stay with the Hopi in 1945, André Breton attended Kachina ceremonies, including Clown dances (the gluttonous Koyala) in the village of Mishongnovi on the Second Mesa. In his "Travel Notebook Among the Hopi Indians," he notes: "The clowns sometimes break the line of dancers, engage in imitations of the shepherd, who frequently pretends to draw from the bow and stands outside the line. They also imitate the corn sprinklers. When the dancers have withdrawn, women bring them countless provisions (breads of all shapes, watermelons, oranges, hard-boiled eggs, orangeade, and gray candies shaped like rolls of paper, called piki). They break the watermelons by dropping them from a height and occasionally bombard themselves with the pieces. They pretend to build a miniature 'toilet' with a bush, after long debates about its location. Each clown goes off in a different direction; one brings a broken crate, another an old magazine, on the pages of which engravings of fashion can be glimpsed. The third takes from his belt a European-style doll hanging on his back and seats it in front of the bush, to which they also attached necklaces, etc. They tend to impress the children, to provoke their disapproval by acting like them to the extreme. Hence their gesticulation and constant chattering, and their eating like pigs (digging with their hands into the watermelon, all drinking from the same bottle, spilling the offered orangeade on the doll). They pounce on the drum character, pull off his head cabochons, insert into his eyes the two ears or horns they carry hanging: the drum continues to play undisturbed."

The Kachina presented here is a representation of Koshare, the Hano Clown Kachina. It plays the role of a disruptor or troublemaker during ceremonial dances, teasing the Guard and Whipper Katsinam, mocking other dancers, and bringing humor to the spectators.

The Clowns played a significant role in Hopi ceremonies. Beyond the theatrical and comedic aspect of their appearance, they allowed the Guards and Warriors to maintain order and embody justice and wisdom. While the Guards often prevailed, there were instances where the Clowns got the upper hand, causing disorder and confusion at the very the heart of the ceremony.

This is not random but rather symbolically choreographed, illustrating inherent human tendencies. For the Hopi, the Kachina spirit community resembles that of humans: some members strive to conform to established order, while others constantly twist or break the rules. Far from being scorned, the Kachina Clowns are highly respected, feared, and admired. These "Masters of Disorder" represent what Roger Caillois called "the sacred of transgression" ("L’Homme et le Sacré", 1939).

During his stay with the Hopi in 1945, André Breton attended Kachina ceremonies, including Clown dances (the gluttonous Koyala) in the village of Mishongnovi on the Second Mesa. In his "Travel Notebook Among the Hopi Indians," he notes: "The clowns sometimes break the line of dancers, engage in imitations of the shepherd, who frequently pretends to draw from the bow and stands outside the line. They also imitate the corn sprinklers. When the dancers have withdrawn, women bring them countless provisions (breads of all shapes, watermelons, oranges, hard-boiled eggs, orangeade, and gray candies shaped like rolls of paper, called piki). They break the watermelons by dropping them from a height and occasionally bombard themselves with the pieces. They pretend to build a miniature 'toilet' with a bush, after long debates about its location. Each clown goes off in a different direction; one brings a broken crate, another an old magazine, on the pages of which engravings of fashion can be glimpsed. The third takes from his belt a European-style doll hanging on his back and seats it in front of the bush, to which they also attached necklaces, etc. They tend to impress the children, to provoke their disapproval by acting like them to the extreme. Hence their gesticulation and constant chattering, and their eating like pigs (digging with their hands into the watermelon, all drinking from the same bottle, spilling the offered orangeade on the doll). They pounce on the drum character, pull off his head cabochons, insert into his eyes the two ears or horns they carry hanging: the drum continues to play undisturbed."

Explore the entire collection