North America | Arizona

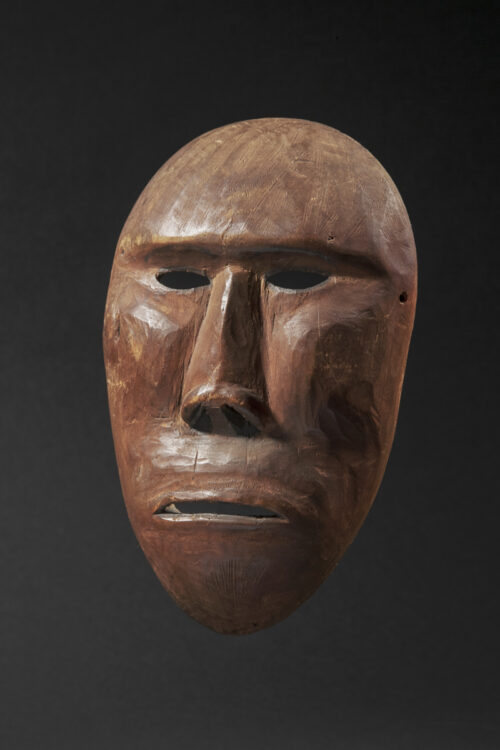

Katsina doll

Arizona

Chusona Katsina – Snake Priest figure

Hopi

Circa 1890-1900

Carved wood (cottonwood), leather and pigments

Height: 26.5 cm – 10 ½ in.

Provenance

Ex collection Alan Kessler, USA

Ex Sotheby’s New York, 4 Dec. 1997 lot 24

Ex collection Galerie Flak, Paris

Ex private collection, France

Publication

“Hopi Katsina, 1600 artists biographies”, Gregory Schaaf, 2008, page 23

Chusona Katsina 26 cm / Galerie Flak

Price on request

Katsina dolls (or katsinam) represent spirits or gods from the pantheon of the Pueblo peoples in the American Southwest. Given to children, Katsina dolls constituted a teaching tool allowing them to familiarize themselves with the spiritual world and perpetuating knowledge of the founding myths on which their society was based.

Pioneering ethnologist Abraham Moritz (Aby) Warburg (1866-1929) was the first to mention the Hopi Snake Dance ceremony. He traveled to the Pueblo region between 1895 and 1896 and stayed among the Hopi. Warburg observed that during the Snake Dance ceremonies, nature is symbolically provoked by a rattlesnake that ritual manipulations (including holding it in the mouth) transform into a catalyst for thunderstorms, bringing beneficial rain.

The Snake Dance takes place in the summer, after the end of the Kachina season, a time marked by thunderstorms and heavy showers. In August, Hopi hunters capture snakes (rattlesnakes and pit vipers) in the desert, which they confine for several days in ceremonial jars kept in the darkness of the kivas, the underground ceremonial chambers. Right before the ceremony begins, the snakes are subjected to smoke to make them drowsy or stunned.

According to Barton Wright, "like all major Hopi ceremonies, the Snake Dance is rich in concepts and symbols and serves several functions. It is primarily a prayer for rain and the cultivation of corn. The ceremony takes place at the end of the summer, when the corn needs rain the most to reach maturity and when the chances of rain are optimal. The warrior aspects are visible in the presence of symbols displayed by the dancers representing Pookanghooya, the Little War God, and traditionally worn by Hopi warriors in battle. Furthermore, the ceremony is related to ancestor worship, as the old members of the Snake Society are represented on the altar during this ceremony."

Dr. Edwin Wade (Museum of Northern Arizona, 1999) adds that the Snake Dance also incorporates elements of two migration stories related to the fraternal priesthoods of the Antelopes and Snakes. The Snake Dance itself occurs on the last day of a more elaborate ritual observance which originally spanned nine days. Preceding the dignified procession of Antelope priests into the dance plaza, the Snake Dancers arrive single file, animated by an aggressive, militant, demeanor. Immediately the Snakes break into units of three dancers, the Carrier, the Hugger, and the Gatherer.

The Carrier, depicted here, kneels before the ceremonial bower, and picks up a snake, which he holds between his lips as he rises and continues to dance. Huggers stand behind the Carrier and often have to "calm" the snake by fanning it with a feather wand. The Gatherer picks up the snake after the Carrier drops it, returning it to the ceremonial bower.

Pioneering ethnologist Abraham Moritz (Aby) Warburg (1866-1929) was the first to mention the Hopi Snake Dance ceremony. He traveled to the Pueblo region between 1895 and 1896 and stayed among the Hopi. Warburg observed that during the Snake Dance ceremonies, nature is symbolically provoked by a rattlesnake that ritual manipulations (including holding it in the mouth) transform into a catalyst for thunderstorms, bringing beneficial rain.

The Snake Dance takes place in the summer, after the end of the Kachina season, a time marked by thunderstorms and heavy showers. In August, Hopi hunters capture snakes (rattlesnakes and pit vipers) in the desert, which they confine for several days in ceremonial jars kept in the darkness of the kivas, the underground ceremonial chambers. Right before the ceremony begins, the snakes are subjected to smoke to make them drowsy or stunned.

According to Barton Wright, "like all major Hopi ceremonies, the Snake Dance is rich in concepts and symbols and serves several functions. It is primarily a prayer for rain and the cultivation of corn. The ceremony takes place at the end of the summer, when the corn needs rain the most to reach maturity and when the chances of rain are optimal. The warrior aspects are visible in the presence of symbols displayed by the dancers representing Pookanghooya, the Little War God, and traditionally worn by Hopi warriors in battle. Furthermore, the ceremony is related to ancestor worship, as the old members of the Snake Society are represented on the altar during this ceremony."

Dr. Edwin Wade (Museum of Northern Arizona, 1999) adds that the Snake Dance also incorporates elements of two migration stories related to the fraternal priesthoods of the Antelopes and Snakes. The Snake Dance itself occurs on the last day of a more elaborate ritual observance which originally spanned nine days. Preceding the dignified procession of Antelope priests into the dance plaza, the Snake Dancers arrive single file, animated by an aggressive, militant, demeanor. Immediately the Snakes break into units of three dancers, the Carrier, the Hugger, and the Gatherer.

The Carrier, depicted here, kneels before the ceremonial bower, and picks up a snake, which he holds between his lips as he rises and continues to dance. Huggers stand behind the Carrier and often have to "calm" the snake by fanning it with a feather wand. The Gatherer picks up the snake after the Carrier drops it, returning it to the ceremonial bower.

Explore the entire collection