North America | Alaska

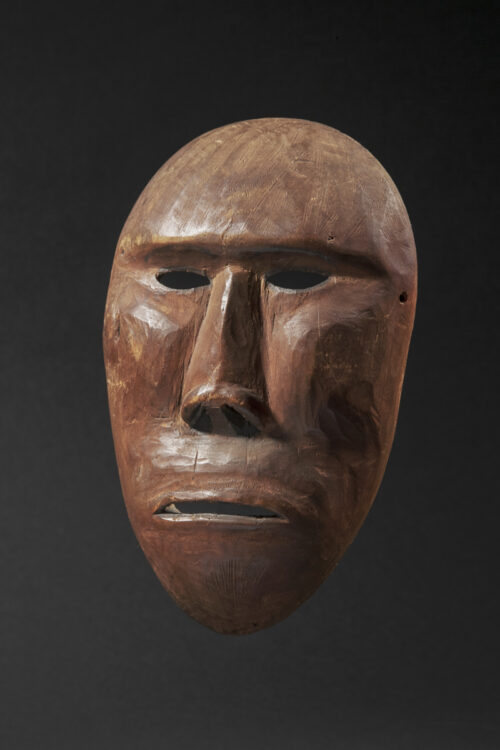

Barbed spear point

Alaska

Bird dart

Okvik, Old Bering Sea I culture

200 BC – 100 AD

Marine ivory

Length: 5 ¼ in. – 13cm

Provenance

Ex Sotheby’s New York, 30 nov. 1995, lot 447

Ex collection Bill & Carol Wolf, New Jersey, USA

Ex collection Donald Ellis, Canada

Ex private collection, France

Ex collection Galerie Flak, Paris

Ex collection Guy Porré & Nathalie Chaboche, Paris

acquired from above

Exhibition and publication

“Gifts from the Ancestors”, Princeton University Art Museum, 2009- 2010, pl. 71 p. 302

“Art of the Arctic, Reflections of the Unseen”, Donald Ellis, 2016, pl. 45 p. 60

Okvik bird dart 13 cm / Galerie Flak

On request

Starting 10 or 12,000 years ago, semi-nomadic hunters ventured across the Bering Strait between Siberia and Alaska, following the migration of large sea mammals. These first Paleo-Eskimo populations progressively established themselves on St. Lawrence Island, a choice hunting ground for walruses and seals. This is where the Okvik / Old Bering Sea I culture emerged around 100 B.C.

Virtually no trees nor plants could grow in the hostile climate of the Far North. Therefore, hunting sea mammals was key to survival. Season after season, century after century, Arctic people have adapted and perfected their equipment and technical know-how.

One of the most salient achievements of engineering in ancient Eskimo culture was the toggling harpoon.

This reusable hunting implement had to be heavy enough to penetrate the thick skin of walruses or seals and short enough to be thrown by a hunter aboard his kayak.

The invention of the harpoon ensured organized, predictable and fruitful hunting expeditions, establishing the foundation for a stable and flourishing culture.

Arctic carvers decorated their hunting gear with shamanic designs to enhance their spiritual potency and maximize their efficacy.

Throughout history, Eskimo cultures have shared the belief that all things in the physical world are imbued with a living spirit, or inua. In order to gain favor with the spirits controlling the animals, a hunter had to approach his prey in a respectful manner. It was believed that decorated objects, through their beauty, attracted the prey and at the same time honored its spirit. Carved depictions of great predators like polar bears or raptors on hunting equipment also helped it find its way to the prey. The harpoon was seen as a traveler between spirit worlds, a messenger between the humans and the creatures of the sea.

Harpoon heads were designed for speed and imbued with a lethal grace. They resemble teeth or talons, a visual means of asking the soul of the animal to give its flesh to the hunter. The finely carved elements of the harpoon served definite functional purposes; they were also endowed with supernatural power. They were passed down from generation to generation and were eventually buried in the graves of important members of the community.

For centuries, the complex belief system of shamanism, allied with masterful technical know-how have guided Subarctic people in the material world and beyond, and have ensured their survival in a hostile environment.

With the help of global warming, present-day Eskimos are able to carry out yearly archeological digs in the permafrost, allowing precious evidence of ancestral hunting practices to be brought to light.

Virtually no trees nor plants could grow in the hostile climate of the Far North. Therefore, hunting sea mammals was key to survival. Season after season, century after century, Arctic people have adapted and perfected their equipment and technical know-how.

One of the most salient achievements of engineering in ancient Eskimo culture was the toggling harpoon.

This reusable hunting implement had to be heavy enough to penetrate the thick skin of walruses or seals and short enough to be thrown by a hunter aboard his kayak.

The invention of the harpoon ensured organized, predictable and fruitful hunting expeditions, establishing the foundation for a stable and flourishing culture.

Arctic carvers decorated their hunting gear with shamanic designs to enhance their spiritual potency and maximize their efficacy.

Throughout history, Eskimo cultures have shared the belief that all things in the physical world are imbued with a living spirit, or inua. In order to gain favor with the spirits controlling the animals, a hunter had to approach his prey in a respectful manner. It was believed that decorated objects, through their beauty, attracted the prey and at the same time honored its spirit. Carved depictions of great predators like polar bears or raptors on hunting equipment also helped it find its way to the prey. The harpoon was seen as a traveler between spirit worlds, a messenger between the humans and the creatures of the sea.

Harpoon heads were designed for speed and imbued with a lethal grace. They resemble teeth or talons, a visual means of asking the soul of the animal to give its flesh to the hunter. The finely carved elements of the harpoon served definite functional purposes; they were also endowed with supernatural power. They were passed down from generation to generation and were eventually buried in the graves of important members of the community.

For centuries, the complex belief system of shamanism, allied with masterful technical know-how have guided Subarctic people in the material world and beyond, and have ensured their survival in a hostile environment.

With the help of global warming, present-day Eskimos are able to carry out yearly archeological digs in the permafrost, allowing precious evidence of ancestral hunting practices to be brought to light.

Publication

Explore the entire collection