Archives | Papua New Guinea

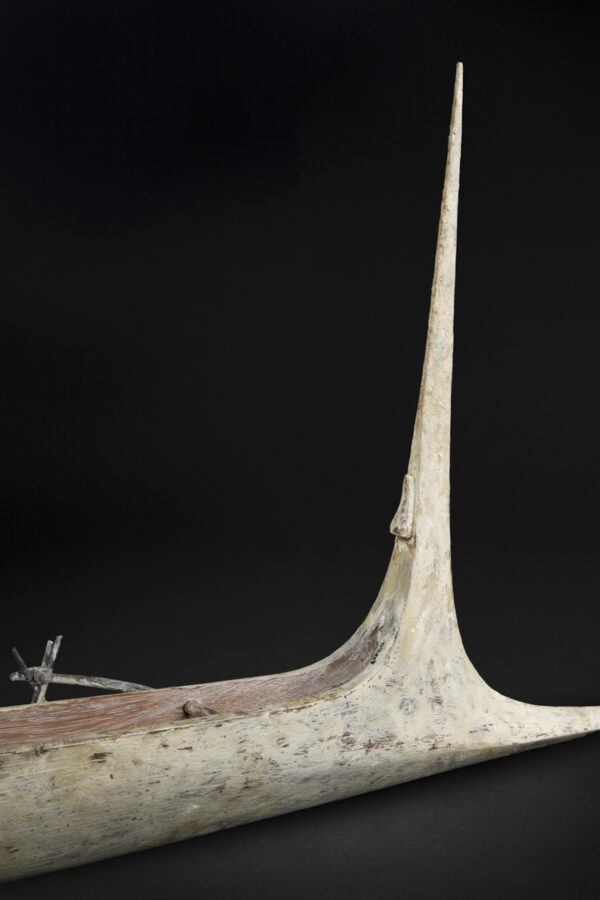

Canoe model

Papua New Guinea

Outrigger canoe model

Wuvulu (formerly Maty Island)

Bismarck Archipelago, Papua New Guinea

Micronesia

Carved wood, fiber and pigments

Early 20th century

Length: 87 cm – 34 ¼ in.

Provenance

Ex collection Serge Schoffel, Paris / Brussels

Ex collection Claude Meyer, Paris

Ex Pierre Bergé & Associés, Paris, 2 April 2012, lot 78

Ex Princely collection, acquired at the above sale

Sold

The canoes of Wuvulu are absolutely unique in Oceania and stand out for the purity of their shape and the finesse of their construction.

Despite being only 100 miles away from the coast of New Guinea, the center of Melanesian culture, the island of Wuvulu—formerly named Maty Island after Matthew Maty, the second principal librarian of the British Museum—is culturally Micronesian. As a result, as noted by the Bowers Museum (California), the unique functional and objects produced on the island show influences from both Melanesia and Micronesia.

Canoes from Wuvulu and its neighboring island of Aua are called wa. They feature outriggers, a sleek, pointed profile, and equally pointed vertical spurs on both their prow and stern.

Wuvulu canoes can vary greatly in size from one person vessels just over 10 feet that are intended for fishing to enormous 60-foot-long ships intended for voyaging by as many as twenty individuals. In some cases, these canoes could be lashed together with their outriggers facing outwards and covered with planks and mats to create a temporary living space. Like the canoes themselves, models from Wuvulu vary greatly in terms of size and scale.

Wuvulu men and women were often expert in different kinds of fishing.

While women worked with nets around artificially contrived holes in the coral reef, men used outrigger canoes for shark-fishing, which was mostly undertaken individually, though the length of some canoes indicates that they were built to carry several men.

Shark-fishers' canoes were dug out from the trunks of breadfruit trees. Peter Brunt and Nicholas Thomas state in Oceania (Royal Academia of Arts, London, 2018): the aluna, the delicate verticals that suggest the fins and tails of sharks, were carved from separate blocks and tied into the hulls, seemingly integral elements of a single form. White limewash, which was regularly reapplied, helped to preserve the vessels. Canoes belonging to a chief were broken up at his death, and their hulls mounted upright, constituting commemorative grave-markers.

Despite being only 100 miles away from the coast of New Guinea, the center of Melanesian culture, the island of Wuvulu—formerly named Maty Island after Matthew Maty, the second principal librarian of the British Museum—is culturally Micronesian. As a result, as noted by the Bowers Museum (California), the unique functional and objects produced on the island show influences from both Melanesia and Micronesia.

Canoes from Wuvulu and its neighboring island of Aua are called wa. They feature outriggers, a sleek, pointed profile, and equally pointed vertical spurs on both their prow and stern.

Wuvulu canoes can vary greatly in size from one person vessels just over 10 feet that are intended for fishing to enormous 60-foot-long ships intended for voyaging by as many as twenty individuals. In some cases, these canoes could be lashed together with their outriggers facing outwards and covered with planks and mats to create a temporary living space. Like the canoes themselves, models from Wuvulu vary greatly in terms of size and scale.

Wuvulu men and women were often expert in different kinds of fishing.

While women worked with nets around artificially contrived holes in the coral reef, men used outrigger canoes for shark-fishing, which was mostly undertaken individually, though the length of some canoes indicates that they were built to carry several men.

Shark-fishers' canoes were dug out from the trunks of breadfruit trees. Peter Brunt and Nicholas Thomas state in Oceania (Royal Academia of Arts, London, 2018): the aluna, the delicate verticals that suggest the fins and tails of sharks, were carved from separate blocks and tied into the hulls, seemingly integral elements of a single form. White limewash, which was regularly reapplied, helped to preserve the vessels. Canoes belonging to a chief were broken up at his death, and their hulls mounted upright, constituting commemorative grave-markers.

Explore the entire collection