Archives | Alaska

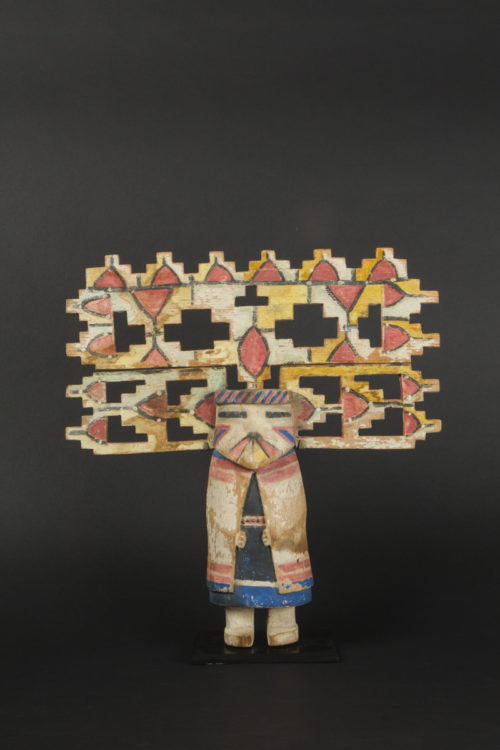

Shamanic Mask

Alaska

Janus finger mask

Inupiaq

Carved wood and feathers

Early 20th century

Height: 2 ½ in. (6.5 cm)

Ex collection Brant Mackley, Santa Fe

Sold

Eskimo culture is characterized by a wide variety of cultural forms, and complex art.

The Subarctic region inhabited by the Yup'ik and Inupiat peoples is well supplied with land and sea resources allowing for much time that could be devoted to a full ceremonial life. After freezeup in the winter, performance cycles were undertaken that were important to maintaining proper human, animal, and spirit-world interactions. Performed inside the qasaiq (communal men's house) during festivals, masked dances took place to give a tangible form to the world of helping spirits and supernatural entities. They were also presented to tell particular stories. Often used by shamans to facilitate communication and movement between worlds (those of the humans and animals, of the living and the dead), masks usually were discarded after use. Finger masks were used to further articulate the important hand movements.

According to Dorothy Jean Ray, Alfred A. Blaker, see Eskimo Masks: Art and Ceremony, 1967: “Inuit masks, which are typically characterized by an abstract and surrealistic aesthetic, should not be considered as 'carvings existing in and of themselves, but as part of an integrated complex of story, song, and dance in religious and secular activities. The art of the mask is concerned with a religious tradition derived from the spirits, and created for them by the shaman. The mask was worn by the shaman when diagnosing the cause of a particular misfortune, such as poor hunting or a crisis in the weather (…). Because dances were performed in order to influence the animal's spirit and therefore its subsequent behavior, it was important not only to make the masks beautiful and exciting, but to select the best dancers to wear them.”

The Subarctic region inhabited by the Yup'ik and Inupiat peoples is well supplied with land and sea resources allowing for much time that could be devoted to a full ceremonial life. After freezeup in the winter, performance cycles were undertaken that were important to maintaining proper human, animal, and spirit-world interactions. Performed inside the qasaiq (communal men's house) during festivals, masked dances took place to give a tangible form to the world of helping spirits and supernatural entities. They were also presented to tell particular stories. Often used by shamans to facilitate communication and movement between worlds (those of the humans and animals, of the living and the dead), masks usually were discarded after use. Finger masks were used to further articulate the important hand movements.

According to Dorothy Jean Ray, Alfred A. Blaker, see Eskimo Masks: Art and Ceremony, 1967: “Inuit masks, which are typically characterized by an abstract and surrealistic aesthetic, should not be considered as 'carvings existing in and of themselves, but as part of an integrated complex of story, song, and dance in religious and secular activities. The art of the mask is concerned with a religious tradition derived from the spirits, and created for them by the shaman. The mask was worn by the shaman when diagnosing the cause of a particular misfortune, such as poor hunting or a crisis in the weather (…). Because dances were performed in order to influence the animal's spirit and therefore its subsequent behavior, it was important not only to make the masks beautiful and exciting, but to select the best dancers to wear them.”

Explore the entire collection