North America | Alaska

Snow Goggles

Alaska

Igauget snow goggles

Inupiaq – Ancient Eskimo

North of the Bering Strait

19th century

Carved wood

Length: 5 ½ in. – 14 cm

Provenance

Collection Karin & Leo (1937-1987) Van Oosterom, The Hague, acquired in 1980

Snow Goggles Van Oosterom 14 cm / Galerie Flak

Price on request

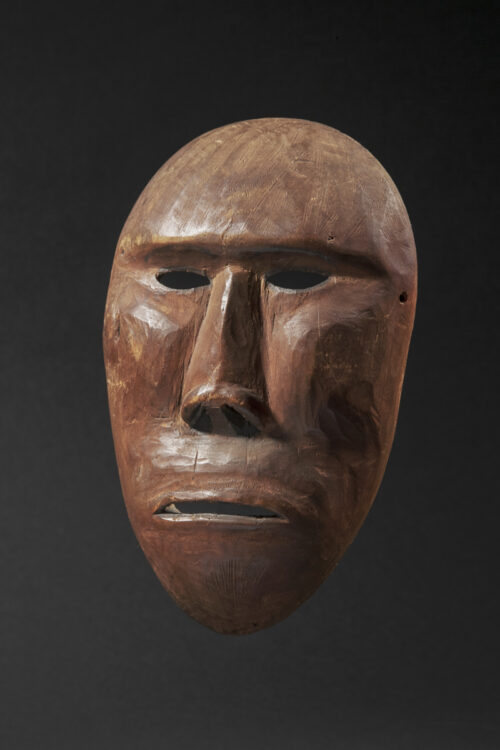

These goggles called "igauget" or "nigauget" in the Yup'ik dialects of Alaska, were carved so as to echo as closely as possible the shape of the face, and minimize luminosity to a maximum – hence the narrowness of the openings for the eyes. The width of these openings had a direct influence on the wearer’s visual field. The more the visual field was reduced, the more visual acuity was accentuated.

Goggles with slits of different sizes were chosen to match climatic conditions (in particular according to the incidence and intensity of the sun’s rays as they varied with the seasons over the course of the year).

Around the beginning of March the returning sun begins to produce a glare on the snow covered Arctic landscape especially north of the tree line. By late April the country acts like a giant mirror reflecting ever more direct bright light.

The goggles varied according to the locality in which they were made and could be carved of wood, often driftwood collected on the shoreline, or whalebone or from the tusk of a walrus.

As noted by Bill Wolf, the harsh Arctic climate presented some unique impediments to the Eskimo hunter. The high latitude left the sun low on the horizon through much of the year, and the resulting glare was compounded by the highly reflective snow or water that covered the area. Without protection, a hunter’s eyes were left vulnerable to a painful and often serious condition known as snow blindness, similar to a sunburn. Ivory or wood snow goggles alleviated this effect by allowing the wearer to peer through narrow openings, while shading him from the excessive glare. Additionally, they afforded protection from wind, sleet, etc. while traveling.

In this artifact, an ingenious utilitarian object is elevated to the level of a work of fine art. These goggles been exquisitely sculpted to fit the contours of the hunter’s face. The economy of line is remarkable.

Goggles with slits of different sizes were chosen to match climatic conditions (in particular according to the incidence and intensity of the sun’s rays as they varied with the seasons over the course of the year).

Around the beginning of March the returning sun begins to produce a glare on the snow covered Arctic landscape especially north of the tree line. By late April the country acts like a giant mirror reflecting ever more direct bright light.

The goggles varied according to the locality in which they were made and could be carved of wood, often driftwood collected on the shoreline, or whalebone or from the tusk of a walrus.

As noted by Bill Wolf, the harsh Arctic climate presented some unique impediments to the Eskimo hunter. The high latitude left the sun low on the horizon through much of the year, and the resulting glare was compounded by the highly reflective snow or water that covered the area. Without protection, a hunter’s eyes were left vulnerable to a painful and often serious condition known as snow blindness, similar to a sunburn. Ivory or wood snow goggles alleviated this effect by allowing the wearer to peer through narrow openings, while shading him from the excessive glare. Additionally, they afforded protection from wind, sleet, etc. while traveling.

In this artifact, an ingenious utilitarian object is elevated to the level of a work of fine art. These goggles been exquisitely sculpted to fit the contours of the hunter’s face. The economy of line is remarkable.

Explore the entire collection