Archives | Democratic Republic of the Congo

Staff

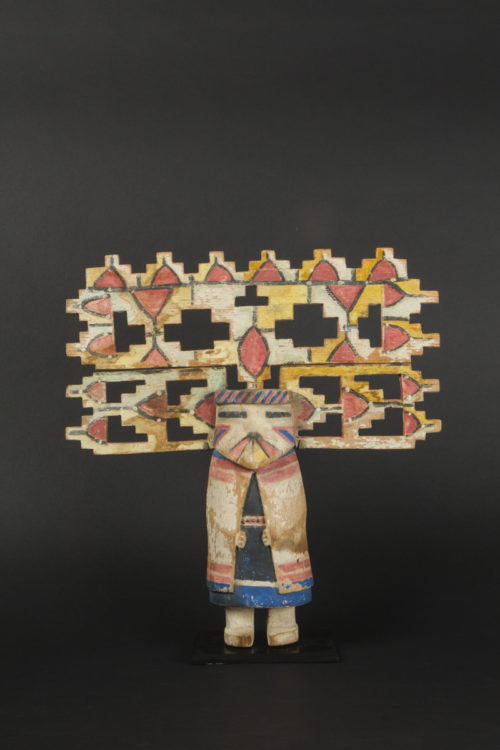

Luba

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Kibango staff

Early 20th century

Carved wood

Height: 26.5 cm – 10 ½ in.

Provenance

Ex collection Pierre Dartevelle, Brussels circa 1989

Ex private collection, Spain

Ex collection David Serra, Barcelona

Literature

« Arts d’Afrique Noire », n. 71, automne 1989 (Adv. L’impasse St. Jacques Arts Primitifs)

Sold

Mary Nooter Roberts & Allen Roberts note in Luba, (2007, p. 38-41) that finely decorated staffs featuring full-length female figures and/or carved heads are called kibango among the Luba people of Central Africa. These ceremonial staffs are part of the Luba regalia. Kibango staffs, transmitted hereditarily, constituted the major insignia of authority for dignitaries. Reserved for members of the nobility, territorial chiefs, and diviners, they functioned as receptacles for the stories, genealogies, and migrations of a family, lineage, or specific chieftaincy.

Female beauty and power is the pervasive theme of much of the artwork of the classical Luba Kingdom. Luba people say that only a woman’s body is strong enough to contain a powerful spirit like a king’s, so sculpture dedicated to kingship is almost always female in gender (quoted by Nooter Robert in Memory: Luba Art and the Making of History, 1996, p. 42). Elaborate hairstyles and complex patterns of scarification on female figures are representative of those actually borne by high-ranking Luba individuals, and fleshy, youthful physiognomy is depicted with flowing, fluid lines and gracefully rounded surfaces.

François Neyt adds in Fleuve Congo (Musée du Quai Branly, 2010, p. 366-367) that the woman secretly watches over the integrity of the royal person, the kingdom, and each village. She undoubtedly plays an economic, social, and political role. She finally appears in the cycle of day and night, the return of the new moon and seasons, in the cycle of life and death. The feminine representation always asserts itself as an initiatory secret. She is the door that opens an elusive reality touching the mystery of existence. "Humanity begins with the navel," says a Luba proverb. This is the key, the opening of the world, the center towards which all forces favorable to fertility and the transmission of generations converge."

The depiction of beauty in Luba Art is of moral and religious significance. Like other Central African sculptural traditions, a figural sculpture was thought to be a locus where a sprit might temporarily settle; for the Luba in particular, the beauty of the sculpture would attract desirable spirits, as would a rich assortment of accoutrements

Female beauty and power is the pervasive theme of much of the artwork of the classical Luba Kingdom. Luba people say that only a woman’s body is strong enough to contain a powerful spirit like a king’s, so sculpture dedicated to kingship is almost always female in gender (quoted by Nooter Robert in Memory: Luba Art and the Making of History, 1996, p. 42). Elaborate hairstyles and complex patterns of scarification on female figures are representative of those actually borne by high-ranking Luba individuals, and fleshy, youthful physiognomy is depicted with flowing, fluid lines and gracefully rounded surfaces.

François Neyt adds in Fleuve Congo (Musée du Quai Branly, 2010, p. 366-367) that the woman secretly watches over the integrity of the royal person, the kingdom, and each village. She undoubtedly plays an economic, social, and political role. She finally appears in the cycle of day and night, the return of the new moon and seasons, in the cycle of life and death. The feminine representation always asserts itself as an initiatory secret. She is the door that opens an elusive reality touching the mystery of existence. "Humanity begins with the navel," says a Luba proverb. This is the key, the opening of the world, the center towards which all forces favorable to fertility and the transmission of generations converge."

The depiction of beauty in Luba Art is of moral and religious significance. Like other Central African sculptural traditions, a figural sculpture was thought to be a locus where a sprit might temporarily settle; for the Luba in particular, the beauty of the sculpture would attract desirable spirits, as would a rich assortment of accoutrements

Publication

Explore the entire collection